Literature

Bitcoin: A Peer to Peer Electronic Cash System (2009) Satoshi Nakamoto

The original ‘White Paper’ of Bitcoin written by the still mysterious Satoshi Nakamoto, the pseudonym used by Bitcoins inventor(s). The paper theorises an online payment system in which electronic cash is sent directly from one user to another without the need for a third-party institution such as a bank. It is now recognised that Nakamoto did more than invent a currency. He also solved a longstanding problem in computing, to do with data and networks. His solution was complex, but it involved the use of an infrastructure comprising “blocks” of confirmed transactions that form a chronologically linked “chain”. This paper is essential reading for anyone wanting to understand the theory behind blockchain and how Bitcoin was born. It is important to note that before every new cryptocurrency is launched, a white paper is written by its creators. A white paper details everything a potential investor needs to know, including the problem the new token intends to solve in the existing market. It is simultaneously a pitch, a business plan and a marketing plan. You can find a data base of white papers here.

This book is incredibly successful in envisioning the future potentials of blockchain technology. Written by father and son duo, Don and Alex Tapscott, Blockchain Revolution sets out examples of changes this technology could bring about. First, they suggest, blockchain technology could transform remittances, the largest flow of funds into the developing world; transfers could take place in an hour rather than a week, and with greatly reduced commission. Second, the technology could provide immutable land title registration for the estimated 5 billion people in the world who have only a tenuous right to their land. Third, it could overhaul online identity, allowing us greater privacy but also the ability to gain value from those aspects of our data we are prepared to share. Finally, blockchain technology could help artists and musicians claim ownership of their work and receive a fair share of its value. But they continuously raise the same questions: Is this blockchain revolution likely?, And is it actually desirable?. The authors acknowledge both barriers to adoption and also dangers. Either way, whether the revolution comes around or not, this book lays out the huge potential that is the blockchain.

Sex, Drugs and Bitcoin: How much illegal activity is financed through cryptocurrencies? (2018)

Is an academic paper by Sean Foley (Senior Lecturer at University of Sydney), Jonathan R Karlsen (PHD student at the University of Technology Sydney) and Tālis J. Putniņš (professor at UTS). The paper discusses the ethics of people investing in currency that is being used to sell drugs, weapons, finance terrorism, forgeries, launder money and sometimes even murder for hire. This is both an interesting and controversial paper because the authors claim that much of Bitcoin’s value is derived from its use as the perfect anonymous trading system for the dark web. They use the analogy that Paypal is to Ebay, what Bitcoin is to the dark-net, in that it is a reliable, scalable and convenient payment method. The authors are trying to illustrate the size of the problem, that whilst Bitcoin has grown rapidly in price, it has also facilitated the growth of an illegal market very close in size to the total market value of illegal drugs in the United States. Their primary finding is that close to one half of all Bitcoin transactions are associated with illegal activity. This is an incredibly detailed research paper, nearly sixty pages long, it even shows you examples of what illegal drugs can be purchased with Bitcoin on the Silk Road. It is also one of the most recent sources of data that is available (January 2018) on the correlation between Bitcoin and the dark web.

The Internet of Money (Volume One) (2016) by Andreas M. Antonopolous

Much of the existing literature on cryptocurrencies focuses on the how of Bitcoin. Technologist, Bitcoin advocate and computer scientist, Andreas Antonopoulos’s book, The Internet of Money (2016) focuses on the why. The Internet of Money is a collection of talks he has given around the world from 2013 to 2016. Antonopolous is not afraid to make bold claims such as Bitcoin is, “the most important technological invention in computer science of the last 20 years”. He also recognises there are many critics and skeptics but compares it to the early stages of the internet when there were also many critics and says Bitcoin is still in its early stages of development. The book does have some flaws such as the fact that because it is a collection of talks there is some repeated material but it is well worth reading as it is much more interesting and insightful than a lot of other material on Bitcoin. The other great thing about this book is that it is available on audible to listen to in the car or at home!. You can also listen to his TedTalk here.

Digital Gold: Bitcoin and the inside story of the misfits and millionaires trying to reinvent money (2015) by Nathaniel Popper

Nathaniel Popper is a New York Times Reporter that has written a novel that provides an indepth history of the early days of digital currencies including experiments such as ‘Digicash’ and ‘hashcash’ and the people who played with the ideas behind it, ‘cypherpunks’. Popper tells the story of the currencies earliest investors including Argentinian entrepreneur Wences Cesares, Silk Road owner Ross Ulbricht, the Winklevoss twins and many more. Most interestingly, it gives a global perspective of Bitcoin, not just how the currency is effecting the Western world, but also the developing world. Popper makes the point that for countries like Argentina, where pesos are so unstable and China where taking money out of the country is restricted, cryptocurrencies are even more important. It also delves into how China wrestled with the decision to make cryptocurrencies legal or illegal. This book is a good place to start for anyone wishing to know more about Bitcoin.

Industry Sources

CoinDesk is probably the largest industry specific website that exists for all things cryptocurrency. It includes every ‘how to’ you would ever need to start trading, mining, and even how to accept bitcoin payments for your store. It also releases a quarterly report on the state of blockchain, detailing any updates, future projections and the current state of the industry. CoinDesk also hosts the largest annual blockchain technology summit in the US, Consensus, raking in at least $17 million in ticket sales alone. The Consensus conference is said to push the price of Bitcoin skyward exponentially, in 2017 the Bitcoin price spiked by 69% during the Consensus conference.

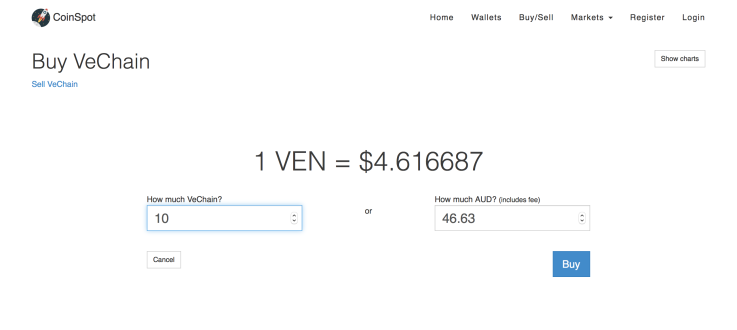

CoinSpot is an Australian cryptocurrency exchange where you can buy and sell Bitcoin, Ether and over 60 different alt coins. BTC markets is often considered Australia’s most popular platform however traders only have the main 6 coins to pick from. CoinSpot also gives you the ability to buy alt coins directly using AUD, whereas on BTC markets, traders have to first use Australian dollars to buy Bitcoin and then buy the alt coins with a Bitcoin trading pair. For example, the “trading pair” ETH/BTC (Ethereum and Bitcoin). Its is also extremely user friendly as it calculates the amount of AUD you would need to buy a certain amount of cryptocurrency, BTC markets does not have this feature.

For example, to buy 10 of the cryptocurrency ‘VeChain’, CoinSpot calculates it will cost AUD$46.63.

Telegram Messenger is an instant messaging service for all your questions about cryptocurrency. It is the most used messaging app in the cryptocurrency community with 84% of blockchain-based projects having an active Telegram community. It has become the universal communications hub for crypto enthusiasts, for sharing news and tips. It is a secret chat that uses end-to-end encryption, meaning nobody but the sender and recipient can read the messages, not even the Telegram staff. For anyone who is hooked on the cryptocurrency world, Telegram is a great communications platform outside of typical social media.

News Media

Women in Cryptocurrencies Push Back Against ‘Blockchain Bros’ (2018)

This New York Times article discusses the contradictory nature of the blockchain and virtual currencies originally meant to be a force of equalisation and democratization, has now become a male dominated culture. The article echoes similar sentiments felt in other sectors of the technology industry where women are decidedly a minority. The article also discusses current attempts to try and get more women into the world of investing because the start of a new technology is often where the big money is made, the winners then decide who to invest in and what to build next. Its an extremely important article about the realisation of a scarily boring and unequal future if the current trends persist, just 4%-6% of cryptocurrency investors are women.

Cryptocurrency Regulation in 2018: Where the World stands Right Now

Regulation is one of the biggest words in the world of cryptocurrencies right now, this article, published in Bitcoin Magazine, covers 15 different countries treatment of e-currencies from the US to South Africa, Ghana, Russia and lots more. Its important to know how different countries are reacting to the rapid growth in order to get some insight into the future of not only regulation but also taxation which is something traders are starting to think about.

Podcasts

The Bad Crypto Podcast is a crude, comedic podcast created by two guys who are both technologists and crypto-enthusiasts but admit they are also learning as they go. This is a great podcast for beginners because the hosts don’t use abrasive, technical speak that often alienates those people that are new to the central ideas and concepts. They explain concepts like Bitcoin mining and how to use exchanges in a really easy to understand format, but they also just have a lot of fun which is a pleasure to listen to. Their success has been huge for how recent it is, their first podcast aired in July 2017 but have already had interviews with people like John McAfee, once the founder of software company ‘McAfee’.

Unchained: Big Ideas From The World of Blockchain and Cryptocurrency

Unchained was created by Laura Shin, a senior editor at Forbes Magazine. In such a male dominated field, its great to have a female voice asking the tough questions and she also talks about gender related issues in the crypto world, such as the fact that nearly all the people who write code for cryptocurrency are men. Her position at Forbes means she is privy to interviewing some of the top authorities in the business and finance sphere as well as entrepreneurs, investors and thinkers. Unchained is a bit more advanced and technical compared to Bad Crypto, it goes into more depth about different types of cryptocurrencies and interestingly talks a lot about governance. The only downside to Unchained is that new episodes only come out once a fortnight which is a long time in the world of cryptocurrency.

Twitter is a great source of information for any topic, but especially for crypocurrencies!. All the big names in the crypto world use twitter as their main form of communication on a public platform. Some of the best and least annoying accounts to follow are:

@cz_binance https://twitter.com/cz_binance (CEO of Binance.com)

@APompliano https://twitter.com/APompliano (Trader and enthusiast)

@SatoshiLite https://twitter.com/SatohsiLite (Charlie Lee, creator of Litecoin)

Contextual Essay

My interest in cryptocurrencies stemmed from an article I came across in the Law Society Journal of New South Wales titled “The Dark Side of Bitcoin” (March, 2018). The article was about a new research paper called Sex, Drugs and Bitcoin: How much illegal activity is financed through cryptocurrencies? Undertaken by forensic financial analysts at multiple Sydney Universities. The research paper finds a clear correlation between illegal activity on the dark net, such as arms trade, drug trafficking, human trafficking and cryptocurrencies being the anonymous trading system that allows it to happen. This gave me an almost immediate negative opinion of cryptocurrencies, but it didn’t portray the whole story. After further research into the potentials of blockchain technology and the capabilities it presents for a completely decentralized financial system, I realized there was a clear difference between the representation of cryptocurrencies in media as the future of decentralized currency and the reality of the future of cryptocurrencies having to be regulated by governments or third parties.

I looked into the history of cryptocurrencies and the original white paper written by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2009 theorizing an online payment system in which electronic cash is sent directly from one user to another without the need for a third party institution. The need for regulation directly contradicts its original purpose and I started to wonder how this would be accepted or rejected by users of cryptocurrencies.

Originally I thought about creating a podcast as a sort of ‘how to’ on trading and investing in cryptocurrencies, but I realized that many of these videos and podcasts already exist on youtube and other platforms. I also knew that much of the existing literature on cryptocurrencies and the blockchain is overly complicated and confusing for an average person looking to invest or just understand a bit more about it. For this reason my aim was to follow on from a previous ‘Future Cultures’ students digital artifact, @eddiesmedia, who created a succinct library of quality literature, industry research and news media to educate people unfamiliar with the technology behind Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. I think this is important because there is so much speculation, hype, confusion and prophesying surrounding cryptocurrencies that it isextremely hard for the average person to understand the risks, potential uses and history of cryptocurrencies.

Overall I think the finished product presents a good scope of different and helpful media sources, from books, research papers, industry websites, news media, podcasts, and twitter accounts to follow. I wanted the reader to get a grasp of the struggle between those who believe cryptocurrencies will herald the future of money and those who are very skeptical about whether the blockchain revolution is likely and how this will be effected by the impending regulation already being implemented. I would have liked to go more into depth about the history of currency and bookkeeping by providing a source that explains how the system of ledgers transformed banking.

Resources used

Antonopoulos, A 2016, The Internet of Money (Volume One), Merkle Bloom LLC

Allam, K 2018, ‘The Dark side of Bitcoin’, Law Society of NSW Journal, Issue 24, March 2018, p.28-29

Dahlen, M ‘The Internet of Money (Volume One)’ Objective Standard: A journal of culture and politics, Volume 12 issue 4, 2018, p.97-100

Foley, S, Karlsen, J, Putnins, T, 2018 ‘Sex, Drugs, and Bitcoin: How much illegal activity is financed through cryptocurrencies?’ SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3102645

Nakamoto, S ‘Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System’, 2008, https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf viewed April 27 2018

Popper, N 2016, Digital Gold: Bitcoin and the inside story of the misfits and millionaires trying to reinvent money, Harper Paperbacks

Tapscott, D 2016, Blockchain Revolution: How the Technology Behind Bitcoin Is Changing Money, Business, and the World, Penguin Random House